Clinical Features , Diagnosis And Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease:

AETIOLOGY

The causes of Parkinson disease are unknown. Gene mutations have been identified in young onset and familial cases (synuclein, parkin and LRRK2).

Parkinson disease in humans and animals has resulted in increased interest in the role of toxins and an animal model for developing new treatments.

Parkinsonian features may be present in many disorders and are not always treatment (L Dopa) responsive. These disorders usually share features of slowness and rigidity (kinetic rigid syndromes)

1.Parkinson’s disease

- Mimics – Multiple system atrophy (MSA)

- Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)

- Corticobasal ganglionic degeneration

- Diffuse Lewy body disease (DLBD)

2. Secondary Parkinsonism

- Drug induced (dopamine receptor blockers-antipsychotics/antiemetics; sodium valproate)

- Post traumatic (pugilists encephalopathy)

- Vascular disease (small vessel multi-infarct state)

- Infectious (post encephalitic/prion disease/HIV)

- Miscellaneous: hydrocephalus/parathyroid/paraneoplastic

Pathology of Idiopathic

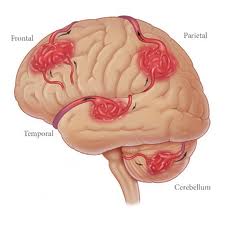

The substantia nigra contains pigmented cells (neuromelanin) which give it a characteristic ‘black’ appearance (macroscopic). These cells are lost in Parkinson’s disease and substantia nigra becomes pale. Remaining cells contain atypical eosinophillic inclusions in the cytoplasm. Lewy bodies may be found in the cerebral cortex especially when dementia is present (diffuse Lewy body disease). Changes are seen in other basal nuclei striatum and globus pallidus.

CLINICAL FEATURES

- Initial symptoms are vague, the patient complains of aches and pains.

- A coarse TREMOR at a rate of 4-7 Hz usually develops early in the disease.

- It begins unilaterally in the upper limbs and eventually spreads to all four limbs.

- The tremor is often ‘pill rolling’, the thumb moving rhythmically backwards and forwards on the palm of the hand.

- It occurs at rest, improves with movement and disappears during sleep.

- RIGIDITY is detected by examination. It predominates in the flexor muscles of the neck, trunk and limbs and results in the typical ‘flexed posture’.

BRADYKINESIA: This slowness or paucity of movement affects facial muscles of expression (mask-like appearance) as well as muscles of mastication, speech, voluntary swallowing and muscles of the trunk and limbs. Dysarthria, dysphagia and a slow deliberate gait with little associated movement (e.g. arm swinging) result.

- Tremor, rigidity and bradykinesia deteriorate simultaneously, affecting every aspect of the patient’s life:

- Handwriting reduces in size.

- The gait becomes shuffling and festinant (small rapid steps to ‘keep up with’ the centre of gravity) and the posture more flexed.

- Rising from a chair becomes laborious with progressive difficulty in initiating lower limb movement from a stationary position.

- Eye movements may be affected with loss of ocular convergence and upward gaze.

- Excessive sweating and greasy skin (seborrhea) can be troublesome.

- Depression occurs in about 50%.

- As the disease progresses the frequency of drug induced confusional states and dementia increases, with 80% developing dementia after 20 years of disease (if they survive).

- Autonomic features occur – postural hypotension, constipation.

- REM sleep behavior disorder – where patient acts out dreams and may hurt themselves or their sleep partner. May precede onset of motor symptoms.

- Time of onset is mid-late fifties with increasing incidence with increasing age. Juvenile presentation can occur, when presentation and disease progression is often atypical; a genetic basis is more often found.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PD in the early stages is difficult. Post-mortem data from the London Brain Bank shows this to be incorrect in 25% of those diagnosed in life.

- New tremor in middle age causes particular difficulty – senile/essential & metabolic tremor generally absent at rest and worsened by voluntary movement.

- The diagnostic use of a L-dopa or dopamine agonist (apomorphine) challenge has decline due to concerns that it may increase the risk of subsequent drug induced dyskinesia.

- Functional imaging (SPECT & PET) should improve diagnostic accuracy and ensure that persons with conditions unresponsive to treatments (PD mimics) are not unnecessarily exposed to them.

TREATMENT

Treatment is symptomatic and does not halt the pathological process. No agents have yet demonstrated convincing neuroprotective effect.

- Levo dopa is given with a decarboxylase inhibitor, which prevents peripheral breakdown in the liver (as in I) allowing a higher concentration of dopa to reach the blood-brain barrier (as in 2) and reduces the peripheral side effects (nausea, vomiting, hypotension).

- Central side effects: confusion, depression, dyskinetic movements and following long-term treatment – ‘On/Off’ phenomenon.

- Rapid onset or longer action can be achieved using dispersible or controlled-release preparations.

- Exogenous dopa improves bradykinesia, rigidity and, to a lesser extent, tremor, but in 20% the response is poor. Dopa has relatively less effect on non-motor symptoms.

- A new preparation of dopa is available for continuous infusion via jejunostomy in severe disease.

- Dopamine agonists: Now used earlier in disease management, they act directly on the dopamine receptor independent of degenerating dopaminergic neurons. It is not clear if patients do better in the long term if dopamine agonists or dopa are used first. There are two types of dopamine agonists, ergot derived, including pergolide, cabergoline, apomorphine and non-ergot derived.

- COMT inhibitors: Entacapone reduces the metabolism of levodopa and is used as adjunctive treatment. Tolcapone is an alternative that can cause hepatic toxicity; it requires close monitoring.

For you, the patient or carer, we hope our website www.branerpainclinic.com covers any question you may have regarding Parkinson’s disease in your life. However, if you can’t find quite what you’re looking for – or you would like to know more – please feel free to Contact Us at our clinic Braner Pain Clinic and Call Now : 1 (877) 573-1282. We’d be glad to help in any way we can.