Clinical Features And Management of Cervical Spondylosis:

The mobile cervical spine is particularly subject to osteoarthritis change and this occurs in more than half the population over 50 years of ages: of these approximately 20% develop symptoms. Relatively few require operative treatment.

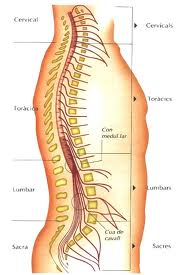

Resultant damage to the spinal cord may arise from direct pressure or may follow vascular impairment. The onset is usually gradual. Trauma may or may not predispose to the development of symptoms.

CLINICAL FEATURES

RadicuIopathy:

Pain: A sharp stabbing pain, worse on coughing, may be superimposed on a more constant deep ache radiating over the shoulders and down the arm.

Paraesthesia: Numbness or tingling follows a nerve root distribution.

Root Signs:

- Sensory loss, i.e. pin prick deficit in the appropriate dermatomal distribution.

- Muscle (I.m.n.) weakness and wasting in appropriate muscle groups.

- Reflex Impairment / lossC5, 6….. Biceps, supinator jerk: C7……. triceps jerk.

- Trophic Change: In long-standing root compression, skin becomes dry, scaly, inelastic, blue and cold.

Arms: l.m.n. signs and symptoms, as above, at the level of the lesion and/or u.m.n. signs and symptoms below the level of the lesion, e.g. CS lesion: deltoid and biceps weakness and wasting; reduced biceps reflex; increased finger reflex. C3/4 lesions produce syndrome of numb clumsy hands (reflecting posterior column loss).

Legs: u.m.n. signs and symptoms, i.e. difficulty in walking due to stiffness; ‘pyramidal‘ distribution weakness, increased tone, clonus and extensor plantar responses; sensory symptoms and signs are variable and less prominent.

Sphincter disturbance is seldom a prominent early feature.

INVESTIGATION

Plain X-ray of Cervical Spine

Look For:

- Congenital narrowing of canal, loss of lordosis.

- Disc space narrowing and osteophyte protrusion (foraminal encroachment is best seen in oblique views).

- Subluxation Flexion/extension views may be required.

MRI: The investigation of choice. Sagittal views clearly demonstrate cord compression at the level of the disc space. Any hyper intensity within the cord on T2 weighting reflects cord damage and may correlate with the severity of the myelopathy and outcome. Axial views show cord compression and the degree of foraminal narrowing.

MANAGEMENT

1. Conservative

Analgesics/Cervical collar: Symptoms of radiculopathy, whether acute or chronic, usually respond to these conservative measures plus reassurance. Progression of a disabling neurological deficit however demands surgical intervention. The clinician may adopt a conservative approach when a myelopathy is mild, but undue delay in operation may reduce the chance of recovery.

2. Indications for Operations:

- Progressive neurological deficit- myelopathy or radiculopathy.

- Intractable pain, when this fails to respond to conservative measures. This is rarely the sole indication for operation and usually applies to acute disc protrusion rather than chronic radiculopathy.

3. Operative Techniques:

(a) Anterior Decompression and Fusion:

A core of bone and disc is removed along with the osteophyric projections. Although not essential, some insert a bone graft from the iliac crest, or a metallic cage to promote fusion. More recently prosthetic discs have become available. There is no evidence that any one technique produces better results than another.

(b) Posterior Approach:

Most suitable for root or cord compression from an anterior protrusion at one or two levels.

- Laminectomy: A wide decompression, usually from C3-C7, is carried out. Appropriate for multilevel cord compression especially if superimposed on a congenitally narrow spinal canal.

- Foraminaotomy: The nerve root at one or more levels may be decompressed by drilling awaver lying bone.

Results

Operative results vary widely in different series and probably depend on patient selection. Some improvement occurs in 50-80% of patients. Operation should be preventing progression rather than curing all symptoms.

If you are being affected by this serious disease Cervical Spondylosis. Braner Pain Clinics specialize in chronic pain management, neurology, neurological testing and disability.

You should call us if you have been advised to learn to live with pain; or have been denied compensation due to an injury for lack of medical evidence. For More Information Call Now at: 1 (877) 573-1282

http://www.branerpainclinic.com

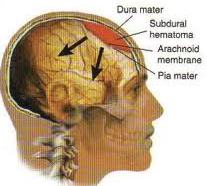

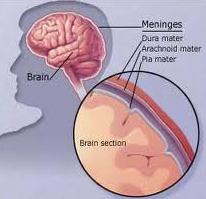

In most cases the infection causing meningitis arises in the nasopharynx intravascular invasion (bacteraemia) and penetration of the blood brain barrier follow mucosal involvement with entry into the CSF. Bacteria may invade the subarachnoid space directly by spread from contiguous structures, e.g. sinuses and fractures. Specific characteristics of the capsule determine whether meninges are breached. Humoral defences against bacteria are absent in the CSF offering little resistance to infection.

In most cases the infection causing meningitis arises in the nasopharynx intravascular invasion (bacteraemia) and penetration of the blood brain barrier follow mucosal involvement with entry into the CSF. Bacteria may invade the subarachnoid space directly by spread from contiguous structures, e.g. sinuses and fractures. Specific characteristics of the capsule determine whether meninges are breached. Humoral defences against bacteria are absent in the CSF offering little resistance to infection.